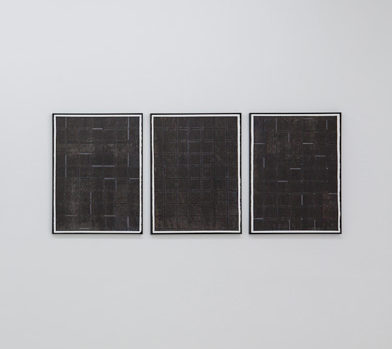

JENNIFER CAUBET | Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle

In situ 20 May 2023 - 16 September 2023Galerie Jousse Entreprise is pleased to present the second solo exhibition of Jennifer Caubet, Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle, from May 20 to September 16, 2023 (closing from 07.30 to 09.01.2023 inclusive).

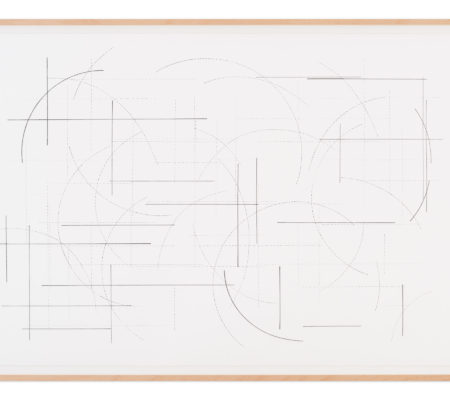

Is it the activation of a space that builds architecture? Jennifer Caubet has long been interested in speculative architecture – sometimes called utopian – like that of the Situationist Constant or like Yona Friedman’s self-planning. Would it be accurate to employ the word utopian knowing that projection, fiction, and anticipation completely affect our relationship to reality? In Jennifer Caubet’s work, utopias have a technical dimension; this passionate knowledge of a language of tools, materials, and processes allows her to explore the ways in which they are embodied by modes of thought and action in reality.

There used to be a tension in her work between the aesthetic codes of minimal art (which asserts itself in its relationship to space) and her interest in these “paper architects” who envisage beyond the conditioning of rigid structures. Yet something seems to have shifted.

In my opinion, her practice as a whole is driven by an unwavering desire for autonomy: are we capable of making our own habitats, huts, or counter-sites? What would justify excluding women from the technical imaginary? Or depriving them of their capacity to freely act on reality? Why are there still gender assignments concerning certain materials, scales, or techniques? Ones that continue to reinforce a binary division between hard and soft, engineering and weaving.

For Jennifer Caubet, there is not only a challenge of surpassing oneself, but also of surpassing the self, implicating the other in a relationship to space: confronting monumental architecture’s authoritarianism or inhabiting the abstraction of a plan that disregards use. Rather than a relationship to power, with which her work has often been associated, it seems more accurate to me to consider modulability, combinatorics, or human scale as key principles for interpreting her approach. How can we write our space with our bodies rather than be subjected by it?

Jennifer Caubet’s work can enter into a historical genealogy of technical appropriation and self-management. We most often associate this autonomy with a male history – one of manuals for building cabins and open-source furniture, from W. Ben Hunt’s How to Build and Furnish a Log Cabin (1939), to Ken Isaacs’ How to Build Your Own Living Structures (1974), to Enzo Mari’s Autoprogettazione? (1974). It is an incomplete history, which has erased the Surrealist artist Dorothea Tanning’s cabin in the Arizona desert (1946) and Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s pre-ecological critique of modernity, and which has borrowed from migrant housing (1955) and the feminist magazine Country Women (1972) that helped guide the independent construction of rural lesbian communities in Oregon.

Is it by chance that the development of the artist’s work led her to progressively integrate contextual and environmental data? Jennifer Caubet currently lives in La Maladrerie in Aubervilliers, an architectural complex created between 1975 and 1989 by the extraordinary architect Renée Gailhoustet, who, with her garden balconies, foreshadowed the present ecological emergency. The residents of this city are currently defending one of the most beautiful examples of a community garden in Île-de-France, which is being threatened by the construction of a solarium for the Olympic Games and a new area for offices and hotels. Having become a Garden to Defend (JAD, Jardins à défendre), these residents have endured eviction and the destruction of workers’ huts, activists’ shelters, and old trees, as well as cultivable land that has been replaced by concrete slabs. When facing violence from the persistent power of the gentrification model and the denial of our ecological crisis, what are the different forms of civil resistance? Jennifer Caubet is attuned to the popular methods of bypassing obstacles and gates to reappropriate access and reintroduce routes, which she compares to the notion of diffraction: the behavior of waves when they encounter an obstacle is to divide and multiply.

Should fences in a public space signify a form of violence – one that separates public and private space, and which reinforces the privilege of those who see the street as a threat – engaged citizens have been able to reappropriate fences throughout collective history as a defense tool or as a conquest of their rights. Based on this gesture of reversal, Jennifer Caubet decided not to manufacture a new structure, but instead to revive this social sculpture by moving gates from a public space to an exhibition space. Installed in this symbolic place, the gate takes on a dual meaning: it is not only circumventable and self-supporting – hinting at the object’s ambiguity, which can form a barricade and privatize a space – but it especially recalls the constructed and transformable nature of public space. The fragility of these privatized borders is exemplified by a gate made of glass, making transparent that what is presented as fixed. The poet and feminist essayist Audre Lorde has said, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” In this same way, the artist’s exhibited weapons that do not have blades, shatter in her attempt to shatter. To do is to also undo.

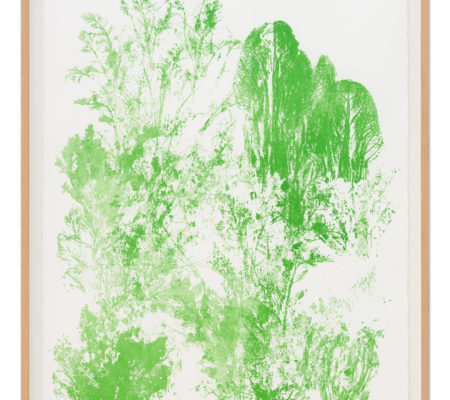

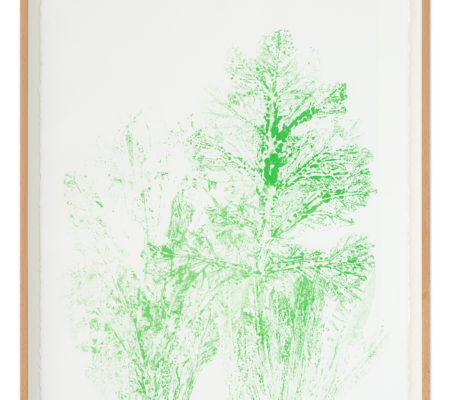

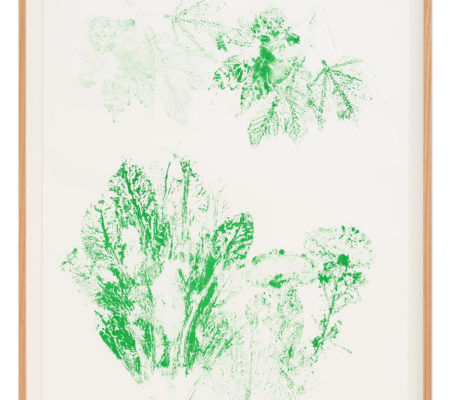

What is being defended? Who is defending themselves from whom? When we observe the protagonists that the artist installed in the exhibition – radish tops, chard, arugula, lettuce, and strawberry plants transposed onto lithographic limestone – we picture the living world’s revolt against a collapse in biodiversity, which would have found allies and representatives in humans, like guerrilla gardening. Echoing research by scholars such as Jocelyne Porcher and Vinciane Despret who are interested in the labor of living beings and in plant and animal life defense strategies, Jennifer Caubet integrates and amplifies a counterattack by living things and non-humans. In the exhibition, Aubervilliers’ community garden thus appears like a ghost, breathing life into the city residents’ power to act.

In referring to Isabelle Frémeaux’s experimental research with ZADs (Zone to Defend) or to the philosopher Joëlle Zask’s thoughts on occupying public squares as a radical form of democracy, the artist furthers the principle of nomadic living structures by using the least amount of floor space. Taking inspiration from a mountain shelter designed by Charlotte Perriand in 1938, Jennifer Caubet retains the frame, its potential, and fundamentally democratic nature. In this gesture, she sums up that what has always motivated her: it is the body – both hers and ours – that writes a space.

Diffractions of the Living World, Pedro Morais

Translation : Terri Morris

Photo Grégory Copitet

Press release (PDF)Vernissage : 20/05/2023 12:00 am

Exhibition's artists > Exhibition's artworks